Exit The Baron, Enter Sandman

How Face helped prompt the save, how Rivera's record-setting career was almost derailed by one sterling start, and how unbreakable is Mo's career save mark

Wins for Elroy Face led to saves for Mariano Rivera.

WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE

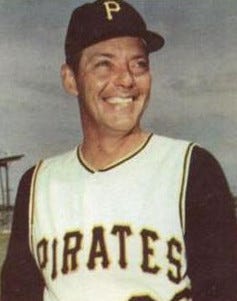

In 1959, Elroy Face amassed one of the gaudiest logs in major league baseball history, winning 18 games and losing just one. The .947 tied the best single season win-loss percentage for pitchers with at least 15 decisions in a single season with Connie Rector of the New York Lincoln Giants in 1929.

However, a young Chicago Sun-Times sportswriter was not impressed. Others, though, were. Face finished seventh in the National League Most Valuable Player voting ahead of such stars as Frank Robinson, who ripped 36 home runs, drove in 125 runs and compiled a .311 batting average and .978 OPS, and Ken Boyer, who hit 26 dingers and knocked in 94 runs with a .309 batting average and .892 OPS. Upon reviewing Face's appearances, Jerome Holtzman learned that the Pittsburgh reliever had allowed the tying or go-ahead run in 10 of his 18 victories.

"Everybody thought he was great," Holtzman, who died in 2008, shared with SPORTS ILLUSTRATED in 1992. "But when a relief pitcher gets a win, that's not good, unless he came into a tie game. Face would come in the eighth inning and give up the tying run. Then Pittsburgh would come back to win in the ninth." (In five of his wins, Face entered with a lead and left without one.)

Although not born of Holtzman's mind--Allen Roth, legendary statistician for the Brooklyn Dodgers, tinkered with the concept in the early 1950s when the Bums had standout firemen in Joe Black, Jim Hughes and Clem Labine--the save now had a loud and passionate advocate with a growing media bullhorn.

In the 1960s, Holtzman, through his pulpit as a regular contributor to The Sporting News, commenced declaration of a "Fireman Award" for the best reliever -- based on reliever wins and his statistic, the save.

In Holtzman's definition, a save had two parts and two exceptions.

Part 1: A save is only awarded when a team wins a game and can only go to a pitcher who does not get the win.

Part 2: A relief pitcher shall not get a save unless he faces the tying or go-ahead run ... with two exceptions.

Exception 1: A relief pitcher does qualify for a save if he comes in with a two-run lead in the final inning and pitches a perfect inning. What is a perfect inning? Three up, three down? Scoreless inning? No walks, no hits surrendered? HHmmm…

Exception 2: A relief pitcher does qualify for a save if he comes in with a three-run lead and pitches two or more innings and finishes the game without giving up the lead.

Through The Sporting News -- and with the support of the Baseball Writers' Association of America -- Holtzman lobbied aggressively to make the save an official MLB statistic. In 1964, the BBWAA officially appealed to both leagues to give the save an audition for a year. The American League tested and quickly abandoned it. The National League passed completely.

In 1969, the save became an official MLB statistic.

However, the save rule adopted was not Holtzman's definition. It was simpler. Much simpler. A reliever earns a save if he enters the game with a lead and finishes the game having protected that lead.

That's it. Nothing about facing the tying or go-ahead run. Nothing about a perfect inning. Nothing to do with exceptions. Hold the lead, get a save.

Traditionalists hated it. And, those who supported it did not like the fact the rule was so loose. No one was happy. Except maybe the relievers, whose livelihood--and bank accounts--would never be the same.

The first year of the save, Fred Gladding of the Houston Astros led the NL with 29 and Ron Perranoski of Minnesota paced the AL with 31.

WAKE UP

In 1974, the rule was modified, closer to Holtzman's vision but, not quite.

Enter a game with the tying or go ahead run on the bases or at the plate and preserve the lead.

Pitch three effective innings while preserving a lead.

Incredibly, this version was received even more poorly than the 1969 initiation. One of my all-time favorite writers and one of the most influential ever, Leonard Koppett (see the name of the blog…) ripped it in a Sporting News column months before the season even began. How to make bad thing worse? Well, by the 1974 rule, a reliever did not have to finish the game to be awarded a save. Yes, again, more than one pitcher could qualify for the save. And, record eight straight outs with a two run lead, fail to finish the game? No save. Pitch three innings of "effective" baseball with a 20-run lead? Save.

Ironically, in 1974, Mike Marshall of the Los Angeles Dodgers became the first reliever to win the Cy Young Award, appearing in a still standing single season standard 106 games, finishing a record 83, earning 15 wins, and compiling 21 saves.

Finally, in 1975, Major League Baseball adopted the rule we know today.

A reliever has to finish the game, only one pitcher can qualify for a save.

Before the relief pitcher needed to face the tying run ... now the rule is…if the tying run is on deck, it's considered a save opportunity.

Presented a three-run lead, a reliever only has to pitch one inning to get the save.

Relief pitchers now had at least a quantifiable, discernible way to measure their contributions. Cue Multi-million dollar contracts. Respect. Specific roles. And, yes, entrance songs.

ENTER SANDMAN

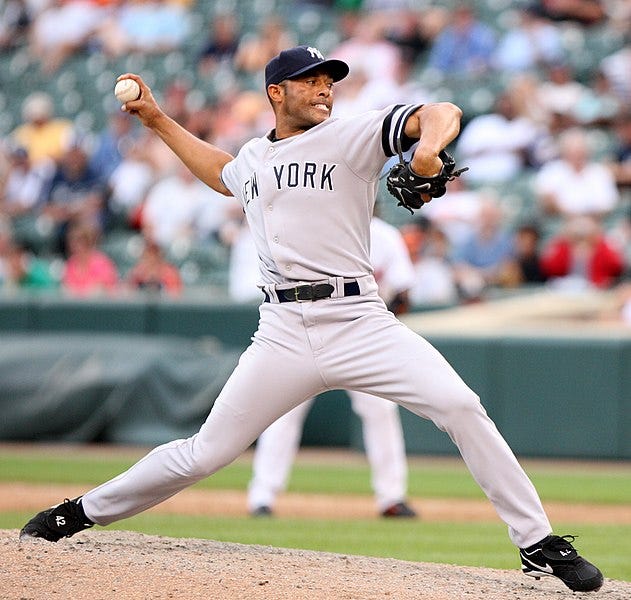

Barely registering on the player personnel radar, on February 17, 1990, the New York Yankees signed an undrafted 20-year Panama native to a $2,000 contract as an amateur free agent.

Although he spent his first year in 1990 at the rookie league level as a reliever, appearing in 22 games, his one start was a complete game shutout.

In 1991, Mariano Rivera appeared in 14 games as a reliever before moving into the rotation. He never set foot out of the bullpen again in the minors, starting 66 games before getting the call to the show in May,1995.

Four starts--a 10.20 ERA, 29 hits surrendered in 15 innings pitched, and high 80s fastball velocity--later, Rivera was back in the minors.

While in Triple-A, Rivera admitted pain. A muscle pull was traced in his shoulder, landing him on the disabled list.

While mending, New York engaged in serious trade talks with Detroit--Rivera for David Wells. But, the Tigers wanted to see if they were getting a healthy hurler. They hesitated.

When he returned to the mound in Columbus, something changed. Rivera threw five perfect innings before a rainstorm ended the game.

Suddenly, inexplicably, Rivera's fastball was clocking at 95-96 miles per hour rather than a top velocity of 91.

Rivera called it a miracle. Yankees general manager Gene Michael called Columbus to confirm the velocity jump. Columbus confirmed and re-confirmed.

Michael then called Jerry Walker, the St. Louis Cardinals' director of player personnel whom Michael knew when they were both scouts.

Michael knew Walker was interested in Rivera and asked about a variety of players before bringing up the righthander. Walker then confirmed all the reports on Rivera. Yes, his velocity was now in the 95 range.

"The next person I called was [then-Yankees manager] Buck Showalter," Michael said to writer Bill Pennington for his book, "Chump to Champs". "I told him, 'We're recalling Rivera to New York right now. I don't know how he did it, but he's throwing 95 in Columbus.

"Then I called [Tigers GM] Joe Klein and told him the deal was off."

LET IT GO

An injured starter prompted Rivera's return to the show in July.

And, on July 4, the righthander enjoyed his best start. Ever. 129 pitches, 11 strikeouts, 2 hits and 4 walks in 8 innings against the White Sox. However, in five subsequent starts, he was never ever able to equal or even approximate that excellence.

So, in September, Rivera moved to the bullpen.

Rivera's 1995 stats? In 67 innings over 19 games, Rivera surrendered 11 home runs with a 1.507 WHIP and a 5.51 ERA. Certainly, numbers that did not suggest he was going to remain in New York better yet become the only player ever elected unanimously to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

But, the Yankees saw something in Rivera.

In 1996, working exclusively out of the bullpen, Rivera flashed the future greatness. Equipped with a devastating and refined cutter to complement his now 95 MPH fastball, in 61 games over 107 innings, he fashioned a 2.09 ERA, .994 WHIP, an 8-3 record, 130 strikeouts, 26 holds, five saves--John Wetteland was the closer--and only one home run. Rivera finished third in the Cy Young voting behind teammate Andy Pettitte and winner Pat Hentgen (remember him? Well, he did win 131 games in his career).

Despite leading the American League in saves with 43, Wetteland was allowed to explore free agency, eventually signing a four-year contract worth $23 million on December 16, 1996, with Texas.

At the age of 27, after five years in the minors and two in the majors, Rivera was now the closer.

In his first season in his new role, Rivera compiled 43 saves along with a 1.88 ERA and a 1.188 WHIP.

For the next 15 seasons, Rivera never dipped below 28 saves in a season, averaging 40 per season. Retiring in 2013, Rivera finished with an MLB record 652 saves, a record that in my estimation, will not be broken or even approached any time soon. Or, ever.

Doubt? Let's look at the numbers.

SMOKE ON THE WATER

In order for a reliever to break Rivera's mark, he would need to average 40 saves a season for 16+ seasons or 30 saves a season for at least 23 seasons.

In fact, 40 saves in a single season has been achieved only 174 times in MLB history. In 2022, only Kenley Jansen (41) and Emmanual Clase (42) eclipsed 40. And, in 2021, not one reliever in the major leagues reached 40 saves. Not one. Mark Melancon led with 39 saves. This was the first time in a non-strike, non-pandemic season since 1982 that at least one reliever did not compile at least 40 saves. Almost 40 years.

Trend or aberration? Hard to tell. Pitchers have more closely defined roles now, but, managers, general managers and fans have low tolerance for a reliever who throws gas on a lead rather than water. A couple of blown saves and you might be the new bulk inning reliever, sixth inning specialist or reclamation project for another team.

Of those 174 instances of 40 saves in a season, 88 different pitchers are on the list. Of those 88 pitchers, 44 did it once, 50%. Once. One 40 save season and done. 22 did it twice and 12 achieved the 40 save milestone 3 times. That means 90% of the pitchers who have tallied 40 or more saves did so 3 or fewer times. Only four pitchers in MLB history have compiled 40 or more saves in a season at least five times--Craig Kimbrel, Francisco Rodriguez (6), and the two leaders in career saves Trevor Hoffman (9 times) and, yes, Rivera (9 times).

For a pitcher to break Rivera's record, that pitcher would have to average 40 saves a season for 16+ consecutive seasons. That's right--40 saves for 16+ straight seasons. Last season, only two pitchers achieved that mark. Two seasons ago, zero. And, only five have done so five times in their career. To catch Rivera, one would need 16.

Or, a relief pitcher would need to sustain a level of continued excellence at maybe a slightly lower excellence rate--say 30 saves a season for 23 years.

How many pitchers have even pitched 23 seasons in a career? 15. In 100+ years of Major League Baseball history. Nolan Ryan threw in 27 seasons and Tommy John 26. And, yes, by the time most reached that longevity, they were not throwing the number of innings they did when they were younger. Rivera earned 126 of his 652 saves after his age-40 season. He recorded 44 saves at the age of 43, a rare level of age advanced excellence.

To say Rivera's saves record is as distant as Hydrus I is an understatement. Andromeda XII might be a more generous approximation. His record is safe. Very safe.

The ironic part? Rivera's career as the most dominant closer of all-time was set in motion--and almost derailed--by one sterling start.

-30-